Introduction

The use of performance-based equity awards with relative total shareholder return (TSR) metrics is on the rise — dramatically so in the last five years. Yet, despite a wealth of public information on key plan design considerations and pitfalls, we continue to observe a number of important and common oversights in the market. Broadly speaking, these oversights fall into two categories: (1) designing an effective peer group and (2) calculating final award payouts. At best, oversights in these areas will create confusion; but at worst, these items can significantly impact final award payouts in unintended ways.

Designing Comparator Groups

Selecting a comparator group for your relative TSR plan is a domain of nearly endless alternatives. Companies can select from numerous published indices and sub-indices (e.g., the S&P 500), or alternatively, they can create a custom peer group on their own. In turn, custom peer groups can be derived from many sources, including compensation benchmarking peers, key competitors, companies with highly correlated stock prices or numerous other subjective factors. All of these possibilities create opportunity and complexity.

On the opportunistic side of things, companies can exercise tremendous flexibility and creativity when developing a peer group for their relative TSR plan. However, flipping to the other side of the coin, companies must also grapple with a number of complex issues to get their peer group mechanics correct. Our aim in this section of the article is to focus on those complex mechanics, including open vs. closed peer groups, the treatment of lost peers, managing international peers, and handling small peer groups.

- Open vs. Closed Peer Groups

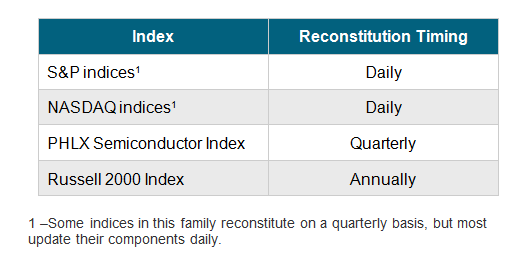

One of the most overlooked aspects of defining a comparator group is also one of the most essential. That is, determining from the onset of your plan if you intend to compete against an “open” or a “closed” peer group. This decision is especially critical when your comparator group is an index. The components of most indices are reconstituted regularly; therefore, the group of companies compromising an index at the end of your performance period is very likely to be different than the companies compromising the index at the beginning of your performance period. Failing to account for these changes can result in radical changes in award values. To illustrate this challenge, the following table highlights the reconstitution rates for common index families used by our clients with open peer groups.

At Aon Hewitt and Radford, we define “open” groups as situations where a company decides to compete against the components of an index that are in place at the end of the performance period. This is to say, final TSR comparisons will be made against final index components, excluding any index components that dropped out of the index during the performance period.

In contrast, we define “closed” groups as situations where a company decides to lock down their comparator group to only those components in place at the start of a performance period. This includes keeping companies that might drop out of an index due to bankruptcy or M&A activity.

Making the choice to use an open peer group means you will subject your company to what is known as “survivorship bias.” Your final award payouts will be computed only against the new and surviving entities of an index, meaning all of the companies that performed well-enough to avoid bankruptcy or delisting from the index.

As a final note, custom peer groups are typically closed by design, and for our part, we regularly counsel clients to close their peer groups that are based on the components of an index. However, there are challenges with this approach, which brings us to our next topic— handling lost peers.

- The Treatment of Lost Peers

If you plan to use a comparator group with a “closed’ model, then it makes sense to define rules for how to handle the treatment of lost peers, usually as a result of bankruptcies and corporate transactions. Lost peers make an impact on final award calculations because they don’t have complete stock price data covering the full performance period. Depending on how you treat these companies, your results can vary.

In bankruptcy situations, there are really only two treatment options to consider. The first approach is to remove the company from the peer group entirely. However, this presents some issues of its own. To start, removing a bankrupt peer means your award holders will no longer receive any credit for outperforming a peer that did poorly. Similarly, when faced with multiple losses due to bankruptcy, your remaining peers will be concentrated toward higher levels of relative performance. These issues often lead companies to consider a second approach for bankrupt peers, which is to set their final TSR at -100%. This places the lost peer at the bottom of the comparator group and accurately represents the TSR observable to a shareholder who invested in the bankrupt company.

Alternatives for corporate transactions are not as clear. While the removal of peers after a merger and acquisition is fairly commonplace when the peer company is not a surviving entity (i.e., a small company similar in scope to your firm is acquired by much larger global firm that faces very few of the same market conditions as you), it’s rare to find cut and dry cases. Mergers of equals and mergers where an acquired peer is the surviving entity require a more hands-on approach, typically with Compensation Committee involvement.

From here, decision makers have several options. They can lock-in available performance data at the time of the transaction, which usually makes sense when more than half of the performance period has elapsed. They can incorporate the surviving company into the peer group. Or they can return to the start of the process and drop the peer entirely.

Based on our experience, we usually counsel clients to consider the following treatment options: (1) should a peer be acquired by another peer, we feel it is best to keep the peer who performed the acquisition and remove the acquired peer; (2) if a peer company merges with or acquires a non-peer and the peer company is the surviving entity, we emphasize keeping the peer; and (3) if the peer company is not the surviving entity after a merger with a non-peer, then the peer should be removed. Going a few steps further, when a peer company spins out a portion of its business but the parent company remains in place, we recommend keeping the peer and treating the spinoff as a re-invested dividend. If the spun out entity replaces the peer company, the peer should be removed. And finally, if a peer is suspended due to misconduct, we recommend applying the same treatment as a bankrupt peer, setting the company to -100% TSR.

- Managing International Peers

More and more performance-based equity awards with relative TSR metrics include peer groups with a global focus. Measuring TSR results across borders creates numerous challenges, including the management of disjointed trading holidays and multiple currencies.

With respect to countries with different trading holidays, this can create confusion if a key date specified by the plan, such as the start of an averaging period, has stock price data for some peers but not for others. This is especially true when averaging periods are defined in terms of “trading days.” For this reason, we recommend that plans with global peer groups define averaging periods in terms of calendar days vs. trading days. By doing so, there is no ambiguity between TSR calculations for domestic and international peers.

Looking next at the currency challenge, TSR results measured in different currencies are subject to exchange rate fluctuations. Exchange rate fluctuations, which can vary widely across countries and time, can artificially inflate or deflate peer performance creating unintended disadvantages or advantages for award holders. The same challenges exist for measuring dividends, which are also paid in local currencies. In order to eliminate the effect of exchange rate fluctuations, we recommend converting all stock prices and dividend payments to your home currency. This is best achieved on a daily basis using the most recently available exchange rates.

Lastly, international peers can force issuers to include a very specific set of clauses into their grant agreements, which you can learn more about by reading our article titled: Managing Relative TSR with Global Peers: The Impact of Currency Fluctuations. These clauses can be avoided if you use American Depository Recipients (ADRs) that serve as domestic currency proxies for international stocks. Unfortunately, ADRs are only available for a limited number of international entities.

- Handling Small Peer Groups

When using small peer groups, it is important to use a payout schedule that is viable for the possible ranks of each company. Too often, we see plans with payout rankings that are not mathematically feasible given the low number of companies in the peer group. For example if your plan has 13 peers, and a payout schedule that pays out from the 50th percentile to the 75th percentile with payout increments at every 5th percentile, your company will not be able to reach the 55th to 59th or 70th to 74th percentile. This issue can be exaggerated if payouts are not linearly interpolated. For this reason, extra testing is required to ensure all payout schedules are mathematically appropriate for small peer groups.

Calculating Final Award Payouts

What’s the difference between a few percentage points among friends? Well, if you’re a property owner with a mortgage, you already know the answer— lots of money. The same holds true for relative TSR awards, where a few percentage points can mean the difference between above and below target performance, potentially totaling millions in earnings across an executive team. When it comes to calculating final award payouts, planning ahead makes a world of difference.

In the following section, we tackle three calculation issues that will almost certainly make a difference in where your award recipients end up. These issues include dividend treatments, averaging periods and grant date timing.

- Dividend Treatments

From the perspective of shareholders, dividend treatments come down to one big question: Do you (1) accumulate dividends and hold them as cash, or (2) re-invest them back into buying more shares? The same decision applies to relative TSR calculations and plans. Accumulating dividends is equivalent to owning a share of stock and choosing to hold dividends received as cash. Re-investing dividends is equivalent to owning shares that are automatically set to re-invest back into the company by buying fractional shares. Fractional shares then appreciate or depreciate in value with the company’s stock price and are entitled to receive additional dividends in the future.

If you choose to re-invest dividends, as most relative TSR plans do, you next need to consider the date on which you make your re-investments. You generally have two valid choices, either the dividend payment date or the ex-dividend date. In our opinion, the ex-dividend date is preferable and should be built into plan designs.

Our reasoning is several-fold. To start, most US exchanges automatically reduce the value of shares by an amount equal to the dividend on the ex-dividend date. Furthermore, by owning stock on the ex-dividend date, a shareholder is guaranteed a dividend payment. All of these items point to the ex-dividend date as the theoretical best choice for reinvestment

- Averaging Periods

Averaging periods are commonly used to smooth out day-to-day fluctuations in stock prices at the beginning and end of performance periods, and are highly advised as a plan design best practice. Using single day stock prices on the starting and finishing dates of your TSR calculations creates significant risk that a performance period may start or end on an anomalous trading day. This single choice could undermine the goal of your relative TSR plan, as long-term performance can quickly become subject to an unforeseen one-day event.

Again, we strongly recommend the use of averaging periods, a point which is backed up by extensive research of more than 600 publicly disclosed relative TSR plans. Based on our analysis, the median averaging period is 20 days across all companies in all industries.

- Grant Date Timing

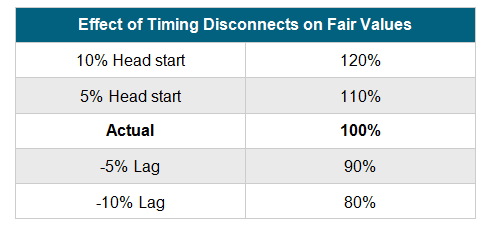

Pursuant to accounting rules IFRS 2 and ASC Topic 718, the movement of a company’s stock price relative to its peers during the time frame between the start of a performance period and the grant date must be incorporated into award valuations. This is analogous to starting a race with a few runners ahead of the start line and a few runners behind the start line. In this scenario, it is more likely that the runners with a head start will finish the race ahead of the runners who started the race from behind.

We observe this effect in our Monte Carlo simulations for companies who grant awards after the start of their performance periods. Large gaps between the grant date and the beginning of the performance period typically result in large impacts on calculated fair values. This occurs because the spread of TSRs becomes larger as the performance period elapses and there is less remaining time for companies to catch up or fall behind. Grant dates closer to the performance period start date have lower impacts on fair values, as TSR gaps are often not as significant and there is ample time to recover. We believe, whenever possible, companies should aim to minimize the time between the performance period start date and the grant date.

As a general rule of thumb, the effect on fair values can be approximated using the table below. This table serves as a useful starting point, but is no replacement for doing the math. The actual effect of grant date timing on valuations can vary dramatically based on several variables.

Conclusion

Relative TSR programs are intended to strengthen links between pay and performance. However, there a large number of technical design issues associated with relative TSR plans that can complicate this task. While many of these issues may seem extraneous at first glance, they can dramatically alter final payout results. Through this article, we hope to alert issuers to common design challenges and pitfalls that should consider from the earliest days of plan design. Tackling the many nuances of relative TSR plan design on day one is far better than confusing award holders and dealing with last minute scrambles to amend plan agreements.

To learn more about participating in a Radford survey, please contact our team. To speak with a member of our compensation consulting group, please write to consulting@radford.com.

Related Articles